|

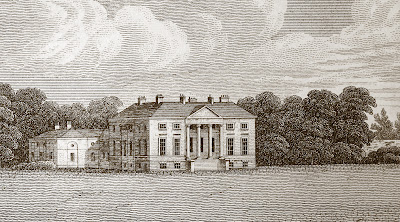

| Stourton Hall Lincolnshire |

The estate at Stourton near Baumber, in central Lincolnshire didn’t have a substantial house before the arrival of the Livesey family in the late eighteenth century. The first Livesey at Stourton who bought the estate was Thomas who died in 1790. His son Joseph rebuilt most of the existing house in 1810 and this later remained as part of the large service wing of the final hall. The brick kiln (cica 1800) on the estate still survives today by the lakeside. The house retained its late Georgian design and stood alone but for a few outbuildings in a 300 acre park until Joseph Montague Livesey inherited the Stourton estate in 1871 at the age of 20. He built the first phase of the new house onto the existing property between 1873 and 1875 using Ancaster stone. The next phase of the plan for remodelling was never completed. Ancaster stone was known for its beautiful light, warm hue and was even chosen for building Westminster palace in the C19th. At Stourton, it was the perfect choice of material for the new Italianate design. Certainly expensive, and impressive as a building material, it was however mined conveniently just 30 miles away and a train line had been operating from Ancaster to nearby Horncastle since 1855.

Stourton hall was unlike many other Victorian Italianate buildings that were more asymmetrical and heavy in design. The style of the windows and surface decoration was entirely based on palladian proportions and gave the building a historic Italian look, also popular in England in the early C18th. The west front which faced the main entrance drive was quite simple and followed exactly the same design for height of windows and architectural features as the south garden front. At ground level one of the windows was larger with 3 openings and two centralised ionic pillars supporting the central pediment. Visitors arriving could be first viewed from this room. There are no surviving pictures of the north entrance front but old map views showing the paths suggest there would have been a doorway in the centre of the main western block of the house. It certainly would have been in keeping with the Italianate designs of the west and south fronts.

The grand south front was topped with a balustrade supporting urns, and most unusual for Lincolnshire, other than at Grimsthorpe Castle, a set of four life-sized draped classical figures. The substantial 90-foot conservatory on the south garden front would have provided the kitchens with a huge variety of food throughout the year. The importance of displaying wealth was important to the Liveseys who were familiar with the grandeur of other houses in Lincolnshire belonging to notable families. In 1903 Algemon Montague Livesey, the Livesey heir married a daughter of the Bertie family of Uffington. The Bertie’s family seat Uffington house unfortunately burnt down the following year.

When Algemon died in 1951 the family decided to sell Stourton. At a time when building materials were highly valued and the running costs of a large house were disproportionate to the dwindling wealth of families facing death duties it was common for family seats to be demolished with little thought for their cultural legacy. In 1953 the house was sold with the entire estate and sure enough was pulled down in 1955. The grand new house had stood for barely 80 years. A few outbuildings and cottage still exist to the north of the estate but unlike many lost country houses, the substantial service wings have also disappeared. The site of the house is now completely wooded over.