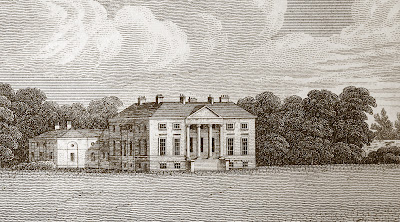

Grainsby derives its name not from farmed grain but from

Scandinavian derivation, the word for branch of a river. The area is covered in

small tributaries to the river Humber. The manor of Grainsby dates back to 1086

and a house would have stood on the estate in various forms for all this time.

Grainsby Hall was once owned by the Nettleship family from Lea, Gainsborough in

Lincolnshire and Francis Nettleship lived there for most of the eighteenth

century and is likely to have been responsible for rebuilding the house from an

earlier structure. Francis left the estate to his servant Elizabeth Borrell who

had actually bought the house and 313 acres for £5,800 in 1795 before his death.

Elizabeth in turn left the estate to her great niece Elizabeth Charlotte who

married a Yorkshire land owner William Haigh of Norland, Halifax in 1827, hence

the subsequent Haigh ownership. The Haigh family were very wealthy throughout

the C18th and C19th centuries and built the Garden Street Mill, the second oldest

in Halifax in 1833, which still exists today converted into flats. They also

owned Castell Deudraeth, a

property in Merionethshire, Wales, known as ‘Aber Iâ’ at the time. The estate

there later became part of the fantasy village Portmeirion by Sir Clough Williams-Ellis.

The family regularly travelled around Britain including London, Wales,

Cheltenham spa and the south coast for holidays. Such was the influence of this

family in business and even politics, George Henry Caton Haigh became High

Sheriff of Lincolnshire in 1912.

Grainsby Hall was rebuilt around the C18th shell around 1860

and is recorded as being photographed in 1863 by Warner Gothard & Co of

Grimsby, although only family portraits from this shoot survive. They chose the

fashionable Italianate style with the main feature being a campanile-style

tower. The design was typically asymmetrical, fashionable in architecture at

the time. The new design was in keeping with the social aspirations of the

family at this time.

The hall was a full household, with the 1881 census showing

the owner George Henry Haigh and his wife Emma, with eight children, seven

domestic servants and a governess. This didn’t include the workers in the

estate cottages or the many farm labourers, stable staff and gardeners. In 1888

a Miss Thomas of Cardiff, one of many subsequent governesses was reported as

successfully taking the family to court over the mischievous behaviour of three

of the Haigh daughters. There are also records of some of the staff prior to

this census. A farm labourer on the Grainsby estate was a

William Taylor (b. 1783 – d. 1859) who married one of the house servants Elizabeth

Wells (b. 1783 – d. 1849) in 1803, and went on to have 10 children between 1805

and 1828. They seem to have grown tired with life at Grainsby as some time

later the couple took a huge risk and took most of their youngest children and

emigrated to Cincinnati, Ohio to start a new life in America. The family soon

spread out and are recorded as having been quite successful. Other workers at

Grainsby took to family life on the estate such as John Barker (b. 1810 – d.

1857 to 1861) a mole catcher who married (after 1840) Ann Dows (b. 1824 – d.

after 1881) a charwoman (house cleaner) and they were both resident at Grainsby

hall in the 1851 census. Their daughter Mary Ann also became a servant at the

hall. John’s elder brother Francis Barker (b. 1802) was a farm labourer at the

hall also in 1851 but had left to become a carpenter by 1861. He also married a

fellow Grainsby hall worker, Jane (b. 1813 – d. 1887) and they had two children

registered as living at the hall although in reality this would most likely

have been in the out houses.

The Haighs were wealthy enough to build beyond

their estate and even constructed Grainsby

Halt railway station 2 miles to the east in 1905 to serve the Hall. This

was closed and demolished some time after 1952. Another notable structure next

to the hall, along the north wall of the kitchen garden, was a huge 100-foot

conservatory which would have been used for the production of food, flowers,

herbs etc, and out of season produce needed to sustain such a large family and

workforce. The walls of the garden and the C18th stable block north of it still

survive. The demise of the hall was typical of so many houses at the time. Grainsby

had been requisitioned by the army during WW2 and fell into disrepair

afterwards when maintenance costs had become unsustainable for the family.

Having been used for some time as a grain store, the building, apparently in a

dangerous condition, especially from the roof and upper floor, was demolished

in February 1973.